The last time I strolled along a trail at the Arboretum, I spotted another fall wanderer — a small black-and-white fuzzy caterpillar. Unlike me, he had a clear purpose in his travels — he was seeking a cozy place to spend the winter. Once he found a sheltered spot — under a log, or in a crevice of bark — he would shed all those fuzzy hairs and use them to craft a snug cocoon. This little fellow was a hickory tussock moth. These moths munch on hickory leaves and the leaves of other plants, but don’t cause a lot of damage to trees.

I’ve always had a soft spot for caterpillars, and when I was a kid, I would have picked him up and maybe put him on a stick and watched him crawl along, just for fun. Seems as though nothing could be more harmless than a fuzzy caterpillar. But I’ve been seeing these little guys all over the media lately— on Facebook, on Twitter, and even on the evening news and in the local papers. And the caterpillars are always described with words like “lethal,” “dangerous,” and “terrifying.” And the scariest word of all: “venomous.” Was I really risking death when I picked up a tussock moth caterpillar in my youth? Are they really a life-threatening menace?

In a word, no. Tussock moth caterpillars don’t bite or sting. They’re not venomous in the sense that a cobra or a scorpion is, with fangs or stingers to inject deadly poisons into humans. The problem is that some of the caterpillar’s bristles are what are called urticating hairs. Like the spines of a nettle, these hairs can cause a rash on sensitive people, but it’s usually a pretty mild irritation. The skin on the palm of your hand is fairly thick, so you’re unlikely to have any problem from picking up a caterpillar. But if the caterpillar brushes against an area with sensitive skin, like your stomach or your neck, an itchy reaction is more likely. So don’t cuddle them against your cheek, don’t put the bristles in your eye. Don’t lick them. (People have done these things.)

It’s not that they’re trying to irritate us. It’s the way the caterpillar survives. When a blue jay grabs a caterpillar for lunch, the caterpillar thrashes back and forth, thrusting the urticating hairs into the bird’s face. The blue jay quickly learns to avoid white, fuzzy food. Later, when the caterpillar pupates, it uses the urticating hairs to make its own cocoon. The soft larva inside the cocoon is defenseless, but the cocoon would be an itchy mouthful for a hungry predator.

So tussock moth caterpillars are certainly not lethal. The warnings about “venomous” and “poisonous” are misleading — “possibly allergenic” is a better term. They will not inject venom into you and kill you.

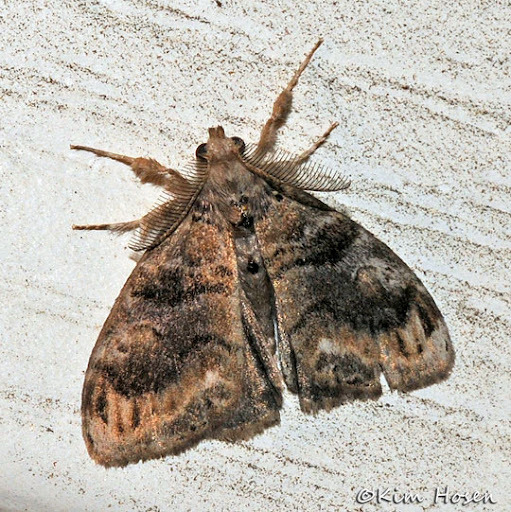

The good thing about these little fellows is that they’re a native species. They’ve been here for millennia. They’re yet another strand in the immense and intertwined food web of the eastern forest. In all their life stages — egg, larva, pupa, adult — there is something that eats them, something that needs them for nutrition. Many woodland birds, like chickadees and nuthatches, are especially fond of insect eggs. The tussock moths belong here.

Knowing all this, try to resist the temptation to squish them or spray them. They grow up into harmless but absolutely gorgeous moths. Think of the beauty we’d miss.