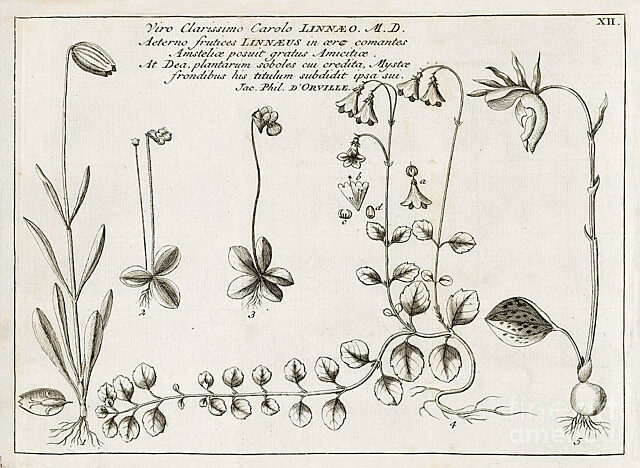

Omnia mirari etiam tritissima.* — Karl Linnaeus

Full disclosure: I was a classics minor.

As an amateur gardener, I am in awe of the Swedish botanist Karl Linnaeus’ system of binomial nomenclature. That would be “bi” (two) + “nomen” (name) and “clatura” (a summoning). His system for naming plants in two words is accepted by botanists worldwide – a universal language, part poetry, part science.

Who could fail to see the poetry in Liquidambar styraciflua? Just say it to yourself and repeat it like a mantra. Liquidambar styraciflua .… (lick-wid-AM-bur stye-ruh-SIFF-loo-uh). It’s “liquidus” + “ambar” (amber) and “styrax” (resin) + “flua” (flowing). American sweetgum. There are several specimens at Landis, with brilliant red star-shaped leaves in the fall and spiny balls of seed capsules. Native Americans used the “sweet gum” of injured trees as a kind of chewing gum and also for medicinal purposes. “Sweetgum” would be understood by those of us in North America, but Liquidambar styraciflua is understood by botanists in all parts of the globe.

Botanists are scientists, and they understand that, under Linnaeus’ system, the first designation is the genus (Latin: clan or tribe). The second term, species (Latin: appearance, shape), indicates the closest related plants.

Before Linnaeus, the botanical world was a confusing welter of common names. Take, for example, those “autumn crocuses” in the Van Loveland garden at the Arboretum. In the English speaking world, they are sometimes called “naked ladies” in the US or “naked nannies” in the UK, since the flowers emerge long after the leaves have died back. In Germany, they are called “Herbsttulpe,” autumn tulips. But in point of fact, they are neither crocuses (Greek, from the word for “saffron”) nor tulips (the Latinized word for “turban,” a reference to where these bulbs originated). The world understands Colchicum autumnale: from Colchis — in Asia Minor where are they are native, blooming in the fall.

And so it goes moving through the Arboretum garden: the common coneflower: Echinacea purpurea: “Echinos” is Greek for “hedgehog,” referring to the spiny core of the flower. “Purpurea” indicates the color purple. “Echinops,” the globe thistle, forms from “hedgehog” + “opsis,” appearance. Geranium sanguinem: the “bloody” cranesbill. As distinguished from common geranium, Pelargonium, from “pelargos” = Greek, “a stork,” referring to the storkbill-like fruit.

Sometimes the names give us clues about the plant’s cultural requirements. The common name “baby’s breath” is certainly poetic enough, a cloud of tiny white blossoms, but Gypsophila paniculata says much more: “lover of gypsum or calcareous soil” + “tufted.” Don’t try to grow this plant in acid soils! “Palustris” means swamp – there are “marsh marigolds” (Caltha palustris) at the edge of several of the Arboretum’s ponds – but they are not marigolds at all! Marigolds are Tagetes, from Tages, an Etruscan deity, the grandson of Jupiter, who sprang from the ploughed earth.

“Repens” will creep. “Scandens “will vine. “Contorta” will be twisted. “Pendula” will be weeping. If you are looking for a plant for a shade garden, “sylvestris” (of trees) will suit your purposes. “Sempervirens” will be evergreen. “Admirabilis” or “elegantissimus” will certainly bring you pleasure. “Officinalis” will have medicinal properties. “Odoratus” will be sweet smelling; “foetidus” will be stinking.

It doesn’t matter if you’ve studied Latin or Greek. Thanks to the genius of Karl Linnaeus, we gardeners all speak the same language!

* Roughly: “Find wonder in everything, even the most commonplace.” Linnaeus’ motto.

Longtime Arboretum supporter and nature educator Anita Sanchez’s children’s book, Karl, Get Out of the Garden! Carolus Linnaeus and the Naming of Everything (Charlesbridge Publishing) is a wonderful gift for any child more at home in nature than in the classroom. Perhaps the best resource for gardeners who wonder why we organize plants by their botanical names at our plants sales (or those who venture along Ed Miller’s Native Plant Trail) is Dictionary of Plant Names by Allen J. Coombes (Timber Press).